I don't know much about the web but I know what I like: art and web IA

View my new website at www.doctordada.com.

This article was originally presented as a paper at the Ark Group Information Architecture Forum, 30 September 2009, Sydney, and at Oz-IA 2009, 3 October 2009, Sydney.

Abstract

The Web is a bit like an art museum: an amazingly rich resource which is too easily squandered. This article introduces principles and techniques used in art museum education and show how they can be applied in web construction, writing and design. Insights are offered into:

- transforming information chaos into information order

- eliminating inessentials

- making personal connections with visitors (or users) through relevance and participation, while minimising cognitive load

- structuring content in terms of what visitors want to know and do, rather than “internal, organisational imperatives”

- the need for unity and consistency, to allow visitors to build up a mental model of the site

- showing a human face, where appropriate.

Matthew Hodgson, in the abstract to his paper, The Evolution of the Agile IA, presented at Oz-IA 2009, wrote:

We [information architects] have stolen from industrial design, borrowed from library science and even bent patterns from theatre and environmental planning to our discipline’s needs... The question is, though, what next? What tools and techniques should we be stealing now?

This article will attempt to provide one answer that question.

Bailed up, by Tom Roberts (right), is one of the Gallery’s most popular works, so if I were a Gallery tour guide, I would have a head start, because most of my work would already be done. All I would need to say would be something like this:

It has been said that Australia had more bushrangers than America had cowboys but when Tom Roberts began this historic romantic painting, its theme was already a thing of the past. The bushrangers who plagued the colony throughout the 1860s were not convict escapees, but 'wild colonial boys', bush- bred youths and young men who combined contempt for authority with a spirit of reckless adventure. Roberts, who arrived from England in 1869, has coupled his ideas about open air realism with the emerging concepts of nationalism which, along with others such as Streeton and McCubbin, helped to create a distinctly Australian school of painting. ...(Yes, it is possible to squander a head start!)

On the other hand, I could ask you...

- What music would go best (or worst) with this painting? Why?

- Imagine it as a video game; give a commentary.

- How would this story have been different if it had been set in the American Wild West?

As I said, we had a big head start with this painting, because it is so recognisable (both in terms of realism and its familiar setting). What happens when we start with something a lot less familiar, such as this semi-abstract painting, by John Olsen (right)? I could ask you...

- Imagine you are walking through the painting with bare feet. How does it feel?

- What would its favourite sport be?

- How would it escape from the Gallery?

- What kind of animal would it be?

Notice that I am not expecting you to know, or even care about, historical context. This is because it is about your encounter with the art object.

What happens when someone encounters an art object?

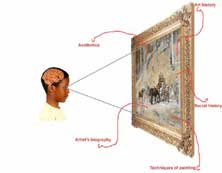

1. According to the traditional way of guiding, what does the art object have to offer? Let us represent each of these with a hook on the end of a thread, stretching out from the painting (right).

- Art history:

“Tom Roberts was one of the founding members of the Heidelberg School of painting, and influenced by English Impressionists, such as James McNeil Whistler.” - Aesthetics (the philosophical/psychological study of beauty):

“The composition has been cunningly constructed with diagonals and verticals leading the eye up to, around and beyond the figures.” - The artist’s biography:

“Tom Roberts was the first major Australian painter to be selected to study at the Royal Academy of Arts which he attended from 1881 to 1884.” - Social history:

“The bushrangers who plagued the colony of NSW throughout the 1860s were bush-bred youths and young men who combined contempt for authority with a spirit of reckless adventure.” - Painting techniques:

“The surface of the painting – scraped, reworked, impasted, glazed, restated – is like a fossilised ocean bed, and traversing its bumps, dents and crevices with the naked eye does not easily expose what is old or new.”

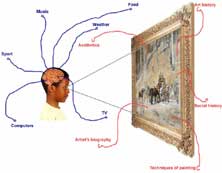

2. What could be going on in the mind of the person doing the encountering? Let us represent each of these with a loop on the end of a thread, stretching out from the boy’s brain (right).

- Food

- TV

- Music

- Sport

- Computers

- Weather

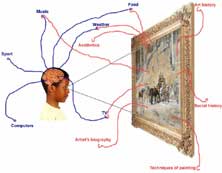

So, to make a connection, I could ask...

- “What would the forecast be for this painting?” (Weather)

- “What would this painting taste like if you could eat it?” (Food)

- “What music would go well with this painting?" (Music)

- “What kind of TV show would this be? (And do you think you’d watch it?)” (TV)

Connections have been made! (See diagram, right.)

In other words, I don’t expect people to know, or care about, historical context, or any of the other “hooks”, not because those things are unimportant, but because, if a connection isn’t made at the start, people will never get to those “other things”.

Relevance to the Web:

- Minimise cognitive load by not expecting the visitor (= user) to know or care about your organisational structure.

- Structure content in terms of what visitors want to know and do.

Here are two exammples, from local government websites:

- Gosford City Council (The naming of links reveals some shaky assumptions.):

- “Water Information Centre” (Why is there a centre for this and not other things?)

- “Electronic Drop Box” (What would I want to use a drop box for?)

- “Council” (Isn’t the whole website “Council”?)

- Brisbane City Council (At least an attempt has been made to group links according to what someone visiting the site might want to do.):

- “I want to...”

- “pay my...”

- “find out about...”

Imagine we are inside the Art Gallery of NSW.

What would junk dropped on the floor need, to be regarded as art, and not just junk? If we just tipped the junk out of a box, it would end up on the floor in a random non-arrangement. Sure, we could place a label and a “Do Not Touch” sign near it, but that probably wouldn’ convince the cleaner that it was, indeed, art. We would need to do something to the junk to make it obvious that it was meant to be there. I call this quality, meantness.

We could...

- Place the junk on a defined area, perhaps within a frame, or on a box

- Line pieces up, perhaps to to an invisible grid

- Choose a colour scheme and remove pieces that don’t conform

Or we could get some advice from artists and/or artworks (often called “style”). So, for example, a Rembrandt painting might give you the idea to place the junk inside a dark, open box and shine a lamp on the centre of the pile. Or, an Impressionist painting might give you the idea of laying a sheet of bubble-wrap over the junk, to soften the colours and blur the edges, so that things blend together.

Meantness correlates to unity, which points to the implied will of the artist.

Relevance to the Web:

- Websites need unity and consistency, to allow visitors to build up a mental model of the site.

- The greatest enemy of unity is incomplete IA [information architecture], followed by a series of pieces of content that “have to be live ASAP”.

Yes, websites need unity, but fortunately websites don't have to all look the same. (See CSS Zen Garden.)

Imagine we are in an artist’s studio.

Imagine we are watching the artist, Peter Upward, painting this abstract painting (right). We can see, by the thickness of the paint, the width and continuity of the brushstrokes, and the absence of downward dribbles, that it was painted with a very wide brush lashed to a stick (or a broom?), loaded with thick, gooey paint, pushed and pulled across a horizontal surface (laid on the floor). The creative act was, by necessity, a very physical and spontaneous one. [However, the artist may have felt the need to make a series of attempts before he achieved a finished product to his satisfaction – thus it is not always a straightforward matter to decide how much time and effort have gone into the making of a work of art.] There is a parallel between our mental re-enactment of the creative process and the exhiliration of watching sport, or dance (we “leap” as they leap).

The trace left by the artist, by the creative process is the human touch.

Relevance to the Web:

- Show a “human touch” where possible.

This principle is most obvious in social media (Facebook, Twitter etc.) but it applies to websites, too. (However, some organisations use, or abuse, Twitter for “official” marketing communications.)

And finally...

It’s not just a parallel between art and the web; it’s also a parallel between the web and face-to-face communication.

So, in conclusion...

- Make personal connections with the visitor.

- Involve the visitor.

- Be human and, if appropriate, light-hearted.

Credits (Left to right): Centerfold by John Oxton, United Kingdom: http://bit.ly/pDg4R; Austrian's Darker Side by Rene Grassegger, Austria: http://bit.ly/ThVNI; First Summary by Cornelia Lange, Germany: http://bit.ly/3hcKMz

Post a comment (on my blog).