“You call that art?”

Have you heard someone say that in an art gallery or museum? Maybe you were the one who said it. What’s behind that question? Actually, it’s more of an accusation, an expression of disbelief that something so far from one’s idea of art could be regarded by anyone as “Art”, and especially that it should be rewarded as such by being exhibited in a recognised art establishment. Often, the sense of outrage is caused by an artwork that doesn’t look like anything or that doesn’t seem to show much skill. So, what is art?

Ask that question of a group of people, including artists, and you will get many different answers, such as:

Art is personal expression.

Art is a way of transcending the everyday.

Art is how the meaningless is made meaningful.

Art is making objects for aesthetic enjoyment, not utilitarian function.

Art is how artists share their delight at the visible world.

Art is the physical representation of an individual’s creativity and imagination.

Art is clarity of expression.

Art is transformation: pulling things apart and putting them back together.

Art is what you can get away with.

Actually, this last answer is a bit of a cop-out, like throwing your hands in the air and saying, ‘There is no answer.’ But it also points to the reason why many people get upset in front of some “art”. They feel that the artist (and possibly the art world) is making a joke at their expense.

Another way of asking the question is: ‘What is art for? What does it do?’

Art’s intrinsic purposes

Before going any further, we should make the distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic purposes. Extrinsic purposes are those that could equally apply to activities other than art – for example, to make money, to win fame and praise, or (in the case of ancient Chinese tomb sculpture) to help the recently dead person in the afterlife). So, what do you think are the intrinsic purposes of art?

After reading and hearing many answers to this question over the years, I have realised that three concepts keep recurring: That art is for…

• creating aesthetically pleasing objects, or

• representing the visible world, or

• expressing emotions.

In addition, artists sometimes use art for experimenting with new ways of creating, representing or expressing.

In fact most artists do all three (or four) at the same time. It would be almost impossible to find an artwork that didn’t show at least a tiny amount of…

- creation (even the most “straightforwardly documentary” and “wildly expressionistic” artworks show some interest in formal qualities such as composition),

- representation (even the most “abstract” artworks have some basis in the visible world) and

- expression (even the most “realist” and “cool” artworks express some kind of emotional state, even if it is just aesthetic delight).

Some examples from art history

When Canaletto painted the piazza of San Marco, Venice (figure 1), his main aim was to describe it as clearly and accurately as possible. Yes, he would also have been aware of the importance of composition. And he probably wanted those who viewed the painting to feel some excitement of the city square and the sparkle of the Venetian light. But mostly, Canaletto was interested in representing the visible world.

When Piet Mondrian painted his Composition no. II, with red and blue (figure 2), he didn’t want to be distracted by the visual details of the world around him. Nor was he interested in “pouring out his emotions”. Instead, he wanted to create a kind of distillation of the universe, using a minimalist artistic toolbox: primary colours, black and white, interlocking rectangles and, most of all, proportion. Of course, even a distillation of the world must retain something of the world. And the meditative, almost mystical state of mind that the artist entered as he painted, and which he hoped his viewers would also feel, is an emotion. But mostly Mondrian was interested in creating an object for contemplation.

Mark Rothko, like Mondrian, wasn’t interested in visual detail. But, by concentrating on colour, rather than geometry and proportion, he shows (figure 3) that he is after a direct, emotional response. So, while the colours may remind us of, say, a city at twilight, and while the composition may be very harmonious, Rothko is mainly interested in the expression of emotion.

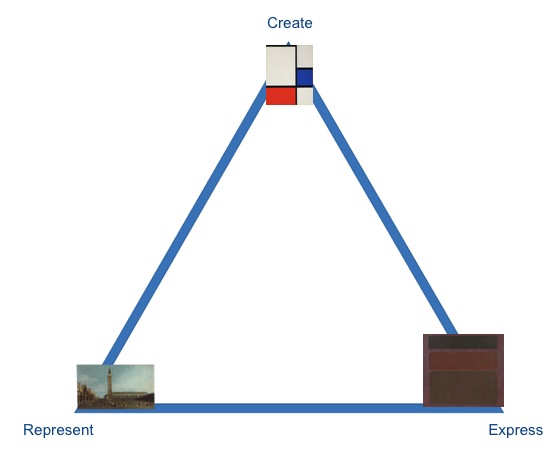

The triangle of artistic purposes

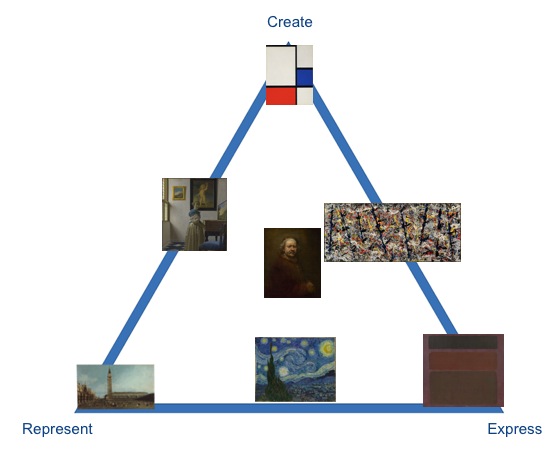

Let’s map these three artists, and their artworks, according to their approaches to art. Because we are interested in the relative proportions of the three intrinsic purposes, rather than any absolute amounts, we can map them on a flat surface, specifically a triangle (figure 4). Each of the three artworks discussed so far sits near (but not quite on) its respective corner: “Represent”, “Create” and “Express”.

But what about an artist such as Johannes Vermeer? His paintings, such as Young woman standing at a virginal (figure 5), are certainly great examples of realist art, especially in the way that the light is depicted. But that is not the main reason that Vermeer is still so highly regarded. It is his composition: the seemingly effortless way that elements are placed against each other, which gives his paintings their sense of quiet perfection. (In fact, many art historians regard Mondrian as the twentieth century Vermeer, or ‘Vermeer without subject matter’ [1]). So, Vermeer’s painting could be placed somewhere between “Represent” and “Create” on the triangle.

Similarly, Vincent van Gogh was responding to a visual experience when he painted The starry night (figure 6), but his imaginative depiction of the scene, particularly the swirling sky, shows that he was prepared to sacrifice a certain amount of visual realism for the sake of emotional impact. So, van Gogh’s painting could be placed somewhere between “Represent” and “Express”.

Jackson Pollock’s Blue Poles (figure 7) is as non-representational as Mondrian’s Composition II, but, unlike Mondrian, its creation was a very physical affair. Pollock applied the paint by flicking, dripping and squirting, as he moved over the large canvas spread out on the floor. While it is hard to match a particular feeling with the finished artwork, the connection between “motion” and “emotion” is not accidental. This is why this style is usually referred to as “abstract expressionism”. So, Pollock’s painting could be placed somewhere between “Create” and “Express”.

There are many artists whose artworks would show more or less equal amounts of all three intrinsic purposes, but one of the greatest would have to be Rembrandt, for example his Self portrait at the age of 63 (figure 8). This painting shows the artist’s concern for visual likeness, emotional truth and compositional rightness. So, Rembrandt’s painting could be placed somewhere in the middle of the triangle (figure 9).

What do you think? How would you have mapped these artworks? Please leave a comment, below.

Mapping artworks on the artistic purposes triangle can be a useful activity for art appreciation. The next time you find yourself looking at an artwork in a museum or in a book, imagine asking the artist: ‘What were you trying to achieve? Were you trying to describe something as accurately as possible? Were you trying to express emotions? Were you trying to create something pleasing to the eye?’ You could even think about how successful or otherwise you think the artist was. This activity is especially effective, and fun, if you are looking with someone else.

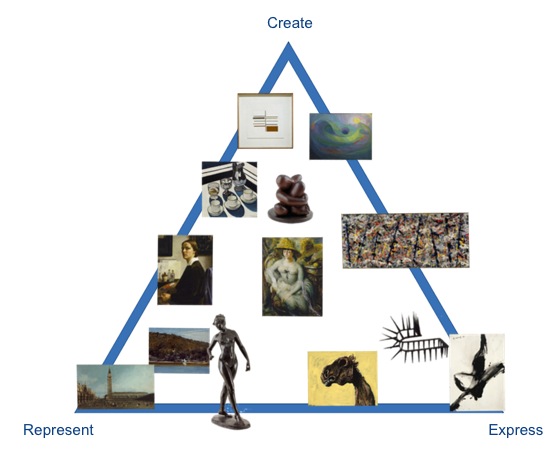

For those interested in a few further examples, here is another version of the triangle (figure 10), with artworks (mostly Australian, including some sculpture) from Australian public collections [2]:

—

1. You might be wondering why would Mondrian bother? Why not include subject matter? Well, imagine a director of a play, who has decided to reject things like sets, props, costume and music, and just present a single actor on a bare stage. If the audience goes away feeling that they have been reached in a powerful way, they would have to know that it was without the benefit of external aids. In the same way, if Mondrian’s painting works for us, we know it can’t have been from our reactions to the subject matter.

2. In fact, all but one is from the collection of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, my place of work for over 30 years.